A Spanish Incursion into the Carolina Backcountry, 1567

by Randell Jones, 2017

Part of the challenge of sharing history is knowing when to start the story. Something always came before. And this story comes from 200 years before Daniel Boone first passed through the Cumberland Gap in 1769.

This story from our experience of becoming America will surprise most people who never suspected a Spanish incursion into the Carolina Backcountry 20 years before the English first landed on the North Carolina coast in the 1580s. Archeology in today’s Burke County, N.C., reveals the story of Joara. Learn more at Exploring Joara Foundation (www.ExploringJoara.org).

Juan Pardo built Fort San Juan in the Catawba River valley in 1566,

At mid-century during the 1500s following Columbus’s accidental discovery of a New World in 1492, French and Spanish kings were contesting for control of North America. Of immediate interest, each wanted to protect or to pirate treasure-laden ships returning to Europe from the Caribbean Sea along the Gulf Stream. In 1565, King Philip II commissioned Pedro Menendez de Aviles to secure Spain’s claim to La Florida’s coastline, running from Key West to New Foundland.

Menendez obliged by massacring the French soldiers at Fort Caroline and then building his Fort San Augustine nearby. In the following year, 1566, he constructed Fort San Felipe at Santa Elena, today’s Port Royal, South Carolina (actually on the Marine Corps’ Parris Island). The French had already abandoned their 1562 Charlesfort there.

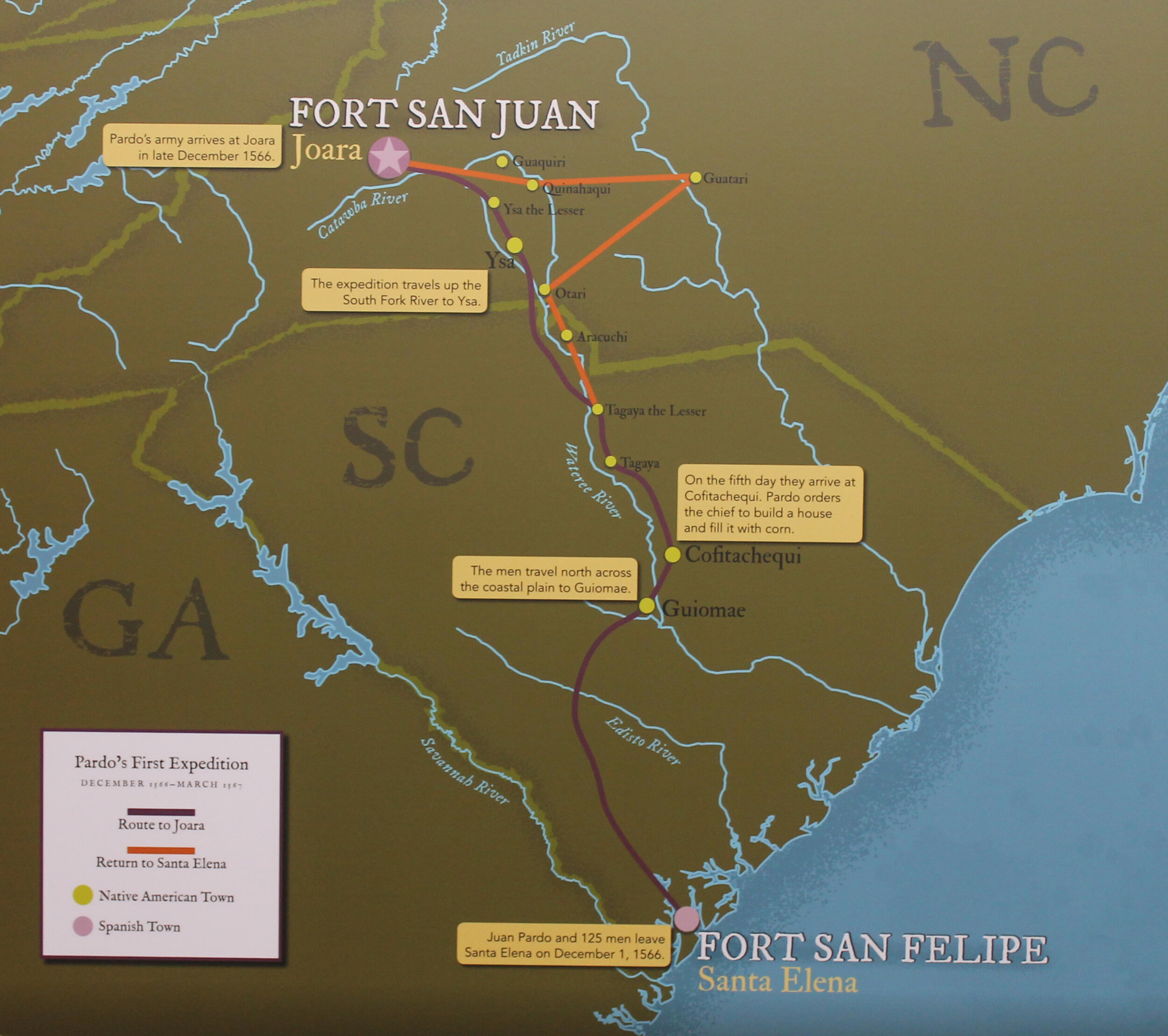

In December, Menendez sent Captain Juan Pardo on an expedition from Santa Elena into the interior of La Florida with 125 soldiers and a priest to Christianize the inhabitants and to secure an overland route to the silver mines in Mexico. (At the time, Spanish explorers poorly understood the continent’s geography.) They trooped upstream along the Wateree and Catawba rivers through the center of today’s South Carolina. Along the way, they visited several Indian villages, exhibiting infamous 16th century Spanish diplomacy. They demanded food and housing; and Pardo informed the natives their land was now Spain’s and they were to follow the Pope.

Juan Pardo arrives at Joara, 1567

(Reenactment at 450th Anniversary: Catawba Meadows Park, Morganton, NC, March 2017)

In early 1567, Pardo entered today’s North Carolina along the Catawba River and turned northwest, likely passing through today’s Lincolnton, and arriving at the principal regional town, Joara, in today’s Burke County. During two weeks, Pardo’s men and Joarans built Fort San Juan, which he garrisoned with 30 soldiers. Pardo and the other soldiers returned to Santa Elena.

Each culture built their worlds with the technologies they had.

Twenty of the Fort San Juan garrison left under Sergeant Hernando Moyano de Morales marched into the mountains and fought against a native tribe, the Chiscas, in today’s northeast Tennessee, killing large numbers of Indians and burning 50 houses. Before Moyano could march again from Fort San Juan in further explorations, a Chisca headman threatened in a message to come over the mountains, to eat Moyano, his soldiers, and his dogs. In April 1567, Moyano, making big trouble for everyone, attacked instead, killing more Indians, destroying villages, and building another fort. In September, Pardo again marched inland, building additional forts and garrisoning men at each.

Soldiers carried matchlock muskets.

“Guests, like fish, begin to smell after three days,” Benjamin Franklin wrote in the 18th century. In the case of Pardo’s forts, the Spanish soldiers soon wore out their welcome. In a coordinated attack in spring 1568, Indian groups assaulted the separate forts, killing all the Spanish soldiers but one. They let him live to warn the Spanish in Santa Elena never to return. The Joarans, ancestors of the Saura, torched Fort San Juan and the adjacent soldier’s village, Cuenca. It is there where 21st century archeological excavations are uncovering this surprising bit of the story or our Becoming America.

Had the Spanish lingered longer at Joara, scholars believe they would have found the gold which sparked America’s first gold rush, in North Carolina in the 1820s. If so, one can suppose quite confidently that our American history would be entirely different.

Learn more at Exploring Joara Foundation (www.ExploringJoara.org).